|

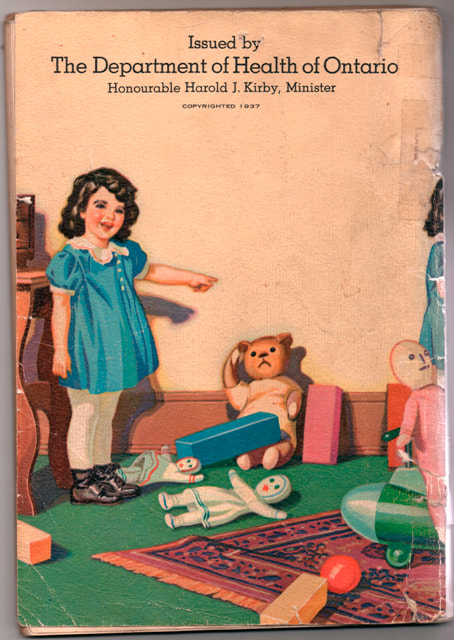

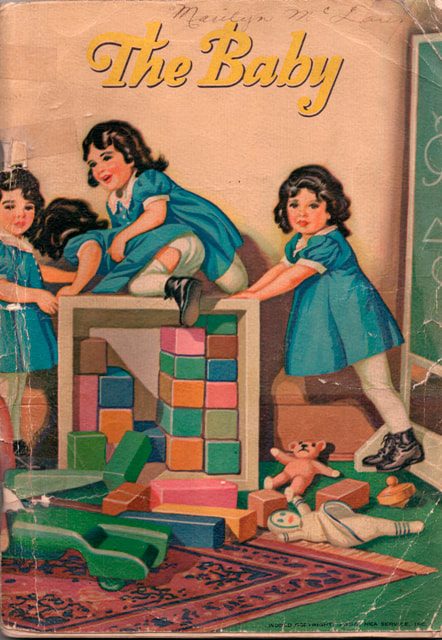

Recently I came across a 1937 booklet issued by the Department of Health Ontario titled The Baby. While very much of its time, babies apparently haven't changed all that much, and it would be quite suitable for today's uberparents to follow. The differences relate more to modern inventions such as monitors, new fabrics, disposable diapers, blenders etc. There's a whole feminist thesis there, but right now I'm thinking about the photographed and painted images used to illustrate proper child rearing of the day. They feature the famous Dionne Quintuplets, a tourist attraction near North Bay, where these five little girls' care was taken over by the province so that they could be raised in a healthy and happy environment while also on daily display in a zoo-like atmosphere. The dramatic story began with the first recorded birth of five babies. After four months with their family, custody was signed over to the Red Cross who paid for their care and oversaw the building of a hospital for the sisters. Less than a year after this agreement was signed, the Ontario Government stepped in and passed the Dionne Quintuplets' Guardianship Act, 1935 which made them Wards of the Crown until the age of 18.[1] The Ontario provincial government and those around them began to profit by making them a significant tourist attraction. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dionne_quintuplets So these beautiful little girls are shown attended by their nurses as they play happily, have their lunch, even get their cod liver oil. (Mandatory for a child growing up in Northern Ontario, cod liver oil has me hating fish to this day.) After being in the spotlight, even media darlings if you will, they were returned to an abusive relationship with their parents, who had had several more children. There is a great deal written by and about the women over the years, but they are generally forgotten these days.

The high irony of using them as examples for a Spock style baby book keeps on giving. It speaks of bureaucratic overload, well-intentioned meddling, exploitation and greed not only on the part of the family but also the government. As a window in time, it also reveals the ways that baby care has and hasn't changed over the decades.

1 Comment

I grew up in a subdivision where we had some Hungarian neighbors. One was my best friend Helen. Whenever I meet someone with any however remote connection to Hungarian-ness I feel compelled to tell them this, along with several other facts such as that I can count and sing in Hungarian, and say a few other words. Without any encouragement I will start in describing the magnificent family picnics I would get invited to, the food that was gradually replacing our previously wasp fare, and what I perceive to be the final kicker, that my cousin had a Hungarian-style wedding since English ones were so dull in comparison. Sometimes I tell until my audience starts to back away. I do know not to follow and continue, although it is tempting. But those picnics! To perpetually starving adolescents they were the most amazing of feasts, where all of Helen's relatives contributed enormous amounts of breaded veal and chicken, mountains of potato salad, cabbage rolls, barbecued meats, cakes, little pastries rolled in nuts and sugar, plums, peaches, of course watermelon. Much of this was homemade and home grown in those wide and treeless subdivision lots. We would play in the warm Lake Erie waves, look for fossils along rocky Morgan's point, then go back for more food. I was a big eater for a skinny kid, and one time, on the way home, Helen's family were joking about this, or maybe just mentioning whether anyone was still hungry, and it came up that there was one veal chop left and would anyone want it. The car was stopped and it was retrieved from the trunk for me to eat. That became one of their family stories that, once I got older, would make me shrink with embarrassment at the telling. The labour market and climate in the Niagara peninsula must have been a major attraction for people coming from Hungary where they could grow the old country fruits and veg. Some were newcomers after the Hungarian revolution in the 50s but the ones we knew were mostly first and second generation families. Nagy and Szabo was as common as Smith and Jones. Everyone had a garden, and everyone made wine. Our neighbour also had a still but we were supposed to keep that a secret. Helen's stepfather John had emigrated more recently, in retrospect he had clearly had a different past life than factory work. He had paintings in the basement, and on summer evenings the crickets and frogs would be upstaged by his haunting mandolin. Language was a barrier - he would grin at us and say things like "Sonofagun" as he polished and polished his car. There was a swing, that he would sometimes push us on, terrifyingly high. When my friend came out of gawky adolescence as quite the beauty, boys started calling her. This would be when John's old country values took over. One memorable event was when he told a would-be suitor to fuck off, then slammed the telephone down. The cultural mashup between old and new is always hard. I am sure it gets played out over and over, but at the time it was pretty shocking. For one thing, fuck off hadn't made its way off the streets and into the common lexicon yet. There was hard work and the struggle of upward mobility while still maintaining the old values. Everyone helped - both parents had factory jobs and older daughter looked after the little ones. This is how I learned things like "Don't touch that" and "go home you dirty pig" as my friend's little siblings were her constant shadow. Despite outside work, her mother still made soup stock with cordon bleu clarity, rows of preserves including peaches, pears, plums, tomatoes, dill pickles. Peaches had to be arranged in the mason jar with rounded halves facing out, perfectly nestled to be beautiful through the glass. The house was also kept impeccably clean. If we walked on a carpet Helen would brush the nap back with her hand to erase our footsteps. We didn't play inside, but I have a clear and happy memory of the two of us playing Monopoly on a blanket in the yard, and her mother bringing out a huge bowl of cherries for us. My memories from this time are all summer ones. We climbed trees in a nearby orchard, we jumped in the hay in somebody's barn. We played in the construction sites where the subdivision was expanding. We rode our bikes. Over the years we have lost touch, but I often imagine Helen as Baba, telling her stories of the white bread English families and their goings on. |

Archives

February 2024

|

Margaret Rodgers | Canada

RSS Feed

RSS Feed