|

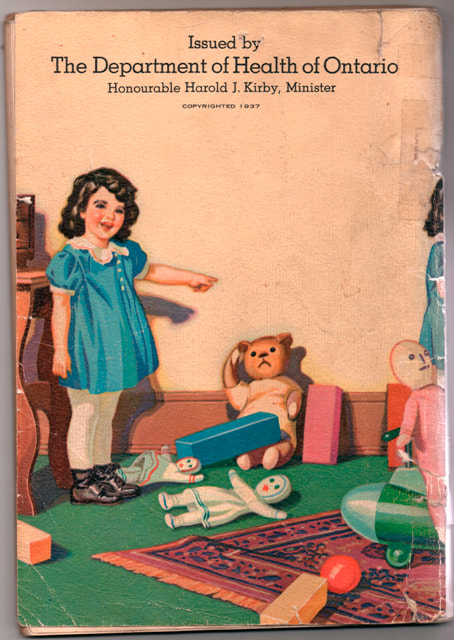

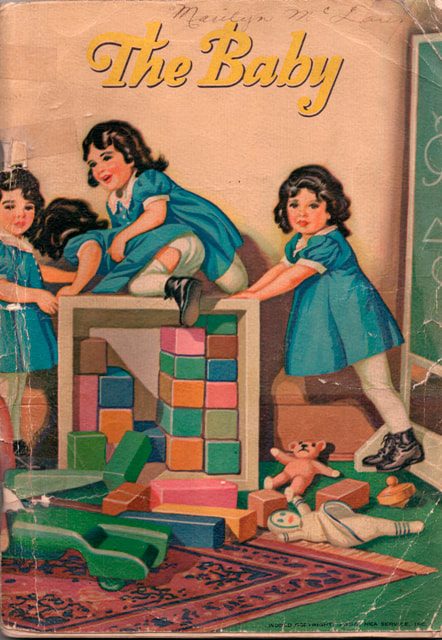

Recently I came across a 1937 booklet issued by the Department of Health Ontario titled The Baby. While very much of its time, babies apparently haven't changed all that much, and it would be quite suitable for today's uberparents to follow. The differences relate more to modern inventions such as monitors, new fabrics, disposable diapers, blenders etc. There's a whole feminist thesis there, but right now I'm thinking about the photographed and painted images used to illustrate proper child rearing of the day. They feature the famous Dionne Quintuplets, a tourist attraction near North Bay, where these five little girls' care was taken over by the province so that they could be raised in a healthy and happy environment while also on daily display in a zoo-like atmosphere. The dramatic story began with the first recorded birth of five babies. After four months with their family, custody was signed over to the Red Cross who paid for their care and oversaw the building of a hospital for the sisters. Less than a year after this agreement was signed, the Ontario Government stepped in and passed the Dionne Quintuplets' Guardianship Act, 1935 which made them Wards of the Crown until the age of 18.[1] The Ontario provincial government and those around them began to profit by making them a significant tourist attraction. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dionne_quintuplets So these beautiful little girls are shown attended by their nurses as they play happily, have their lunch, even get their cod liver oil. (Mandatory for a child growing up in Northern Ontario, cod liver oil has me hating fish to this day.) After being in the spotlight, even media darlings if you will, they were returned to an abusive relationship with their parents, who had had several more children. There is a great deal written by and about the women over the years, but they are generally forgotten these days.

The high irony of using them as examples for a Spock style baby book keeps on giving. It speaks of bureaucratic overload, well-intentioned meddling, exploitation and greed not only on the part of the family but also the government. As a window in time, it also reveals the ways that baby care has and hasn't changed over the decades.

1 Comment

I started this a while back and am reminded to finish it by the recent opening of the Clarington Museums exhibition Rediscovering Identity: The Power of Photography. This is a multi dimensional exhibit that allows visitors to explore many facets of the medium, its mechanics as well as its history. Local artists were asked to interpret a photograph from the archives, so several IRIS members jumped at the chance to do some portraiture and I chose a photograph of what I assume to be two sisters, dressed to the nines and looking a little nonplussed. Special guest speaker at the opening was Steven Frank, who spoke about the history of photography, and showed some 19C - early 20C artifacts such as a stereoscope, wonderful leather bound album, and postcard book. Photographer Jean Michel Komarnicki recently commented that it isn't a photograph until it's printed, and that got me thinking about our existences within Walter Benjamin's famous age of mechanical reproduction. We are rapidly moving out of this era as the evanescent digital age overtakes us, and as the majority of images that we capture never become hard copy. As JMK pointed out, technological changes as well as material degradation of discs may make digital records unreadable in time. And how about those rapidly fading colour prints from the 1960s? Artists are still, of course creating photographs, mostly printed digitally, but with archival considerations. But the family photos that record so much of daily life, special events, travels etc. are mostly shown on screens rather that stored in albums. It is noteworthy, as Frank mentioned, that when disaster destroys peoples' homes the victims invariably mention the loss of those family albums. They tell the stories of our lives and become the stories that are remembered. But they are going. The earliest extant photograph is believed to be "View from the Window at Le Gras" by Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 or 1827. So figuring that by 2025 or so there won't be any more family albums, we can look at this two hundred year period as the age of the photograph. While the latter 20th century will have the richest repository of printed memories, it is possible to look at pictures taken before 1900 and gain a sense of how people dressed, celebrated, wanted themselves to be recorded. Those long exposure times invite an equally long examination of the images. Will future generations have this privilege? |

Archives

February 2024

|

Margaret Rodgers | Canada

RSS Feed

RSS Feed