|

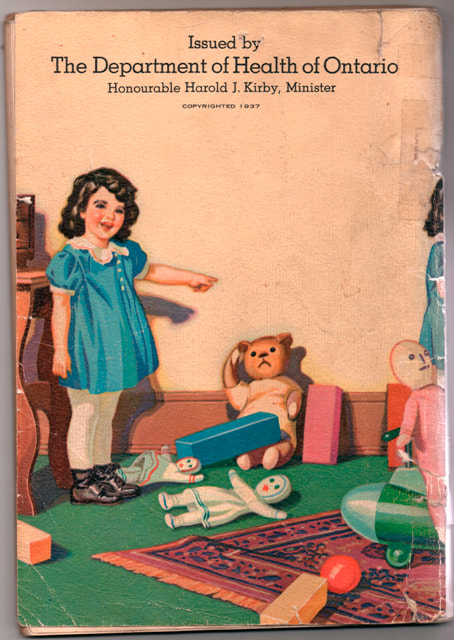

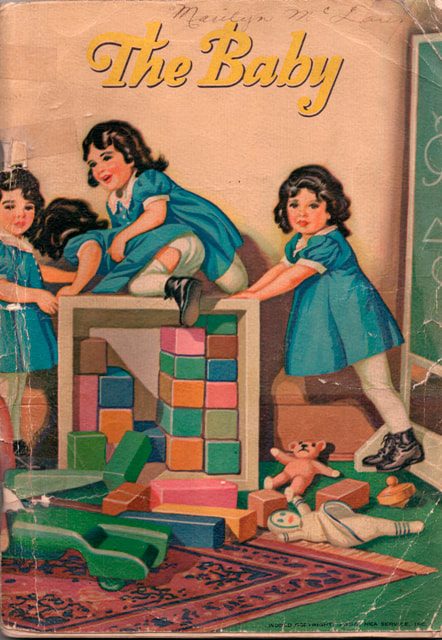

Recently I came across a 1937 booklet issued by the Department of Health Ontario titled The Baby. While very much of its time, babies apparently haven't changed all that much, and it would be quite suitable for today's uberparents to follow. The differences relate more to modern inventions such as monitors, new fabrics, disposable diapers, blenders etc. There's a whole feminist thesis there, but right now I'm thinking about the photographed and painted images used to illustrate proper child rearing of the day. They feature the famous Dionne Quintuplets, a tourist attraction near North Bay, where these five little girls' care was taken over by the province so that they could be raised in a healthy and happy environment while also on daily display in a zoo-like atmosphere. The dramatic story began with the first recorded birth of five babies. After four months with their family, custody was signed over to the Red Cross who paid for their care and oversaw the building of a hospital for the sisters. Less than a year after this agreement was signed, the Ontario Government stepped in and passed the Dionne Quintuplets' Guardianship Act, 1935 which made them Wards of the Crown until the age of 18.[1] The Ontario provincial government and those around them began to profit by making them a significant tourist attraction. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dionne_quintuplets So these beautiful little girls are shown attended by their nurses as they play happily, have their lunch, even get their cod liver oil. (Mandatory for a child growing up in Northern Ontario, cod liver oil has me hating fish to this day.) After being in the spotlight, even media darlings if you will, they were returned to an abusive relationship with their parents, who had had several more children. There is a great deal written by and about the women over the years, but they are generally forgotten these days.

The high irony of using them as examples for a Spock style baby book keeps on giving. It speaks of bureaucratic overload, well-intentioned meddling, exploitation and greed not only on the part of the family but also the government. As a window in time, it also reveals the ways that baby care has and hasn't changed over the decades.

1 Comment

Toni Hamel: The lingering 14 September - 24 November 2013 at The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa Canada Given a long run and two galleries at RMG suggests the importance that the curators attribute to this artist and the thematic direction of her work. Hamel's graphically strong drawings and installations present a forceful narrative on the complications of domestic life in general as well as the psychologically repressive nature of carrying out artistic endeavours on the home front. While this is a feminist story told many times, the necessity for retelling still exists. Hamel delivers a powerful , highly skilled discourse, with content that avoids polemic with dark, subtle humour. The hand of the artist is present, as is the idea of women working with their hands. So-called housewifely tasks are shown in bizarre parody, as images of 1950s style "homemakers" carry out various housekeeping duties that subvert notions of domesticity and underscore its often constricting nature. Women's hands are at work building a nest, decorating an enormous peacock then cheerfully taking it to market in a wheelbarrow, digging in the garden for hearts, working on a child's costume, slicing bread, and so on. Women are shown working together, looking out into a larger world to which there is only imaginary access. Thread and twine are employed throughout, providing a fitting metaphor for gendered constraints. It is also used to extend, accentuate, enhance the finely detailed figurative work on paper and canvas, to define/confine the walls from which one thousand cranes fly forth, to make a cascade of hair that a woman irons industriously, or suggest the skeletal structure of wings that release a kitchen chair from its base where so much domestic work is done. The iconic house image appears in thread in small drawings such as "Attachments" where a woman mows an imaginary lawn, her machine's cord umbilically attached to the house. In other works the thread is a line pulled out of one picture plane into another. In a drawing of a photograph of a woman hanging clothes on a line, a passing bird pulls the clothesline beyond the photo into a freer space. Less whimsically, red thread sews shut a woman's mouth. While the main floor Alexandra Luke Gallery showcases the artist's exquisitely drawn wall works and three major canvas installations, an ascent to the upper gallery immerses one in a world of origami cranes escaping from six houses, into a central nest-like construction made from twigs. An accompanying sound piece of bird cries, gentle whistling, soft giggles, and a beautiful Chopin Nocturne (#9) permeates both exhibition spaces. (audio by Peter Nelis) There is unabashed femininity expressed in the aural and visual content, underscoring the multi-faceted nature of femaleness and of feminism. In general there is a tendency for us to engage in a cognitive dissonance about the role of women within the domestic sphere. There is a comfort level in homemaking that ignores the toll which it has taken in limiting women's lives. Some feminist theory re-evaluates the hand work of women as integral to oral narrative, as safe spaces for discussions, for storytelling, for continuation of a particular cultural environment, for sharing skills, ideas inside a private sphere. However it is clear from the surreal nature of many of the tasks being done by these smiling, busy women that Hamel's intent is to question the validity of repetitive and often meaningless work or, at least, work that is done at the expense of women having richer more creative lives. In her book of essays titled SILENCES, author Tillie Olson mourns the silences‑‑ the literary works unwritten or unpublished because of difficult circumstances and biased ... practices. In The lingering Hamel illustrates the issue with biting humour, skill and warmth. |

Archives

February 2024

|

Margaret Rodgers | Canada

RSS Feed

RSS Feed